|

Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) provides an economic evaluation methodology for assessing the total cost of lifetime ownership of an asset:

The typical steps involved in a life cycle cost analysis are:

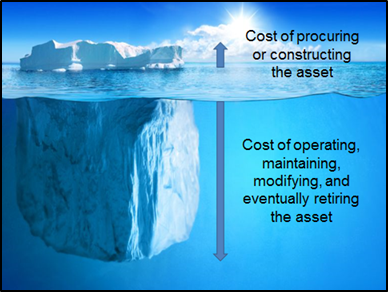

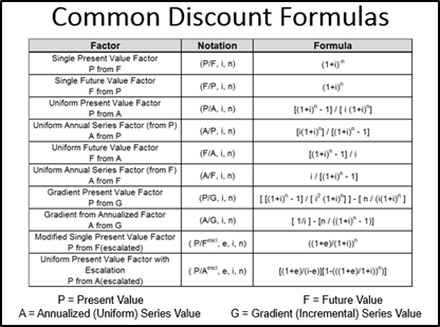

“I am not rich enough to afford cheap things” This well-known proverb is a core principle of life cycle cost analysis, which emphasizes that a lower cost of asset acquisition may not always be the best choice over the life cycle of owning and maintaining an asset. This is true whether the asset we are acquiring is a new car, or a new capital facility to manufacture cars; and is a key focus of AACE International’s Total Cost Management philosophy. LCCA is a methodology that supports an effective comparison between competing alternatives where costs (and benefits) may be spread over an extended life cycle. For the capital project industries, project teams are often focused on minimizing the capital cost of facility planning and construction through start-up of an asset; however this asset acquisition cost may be a small fraction of the total cost of ownership of the asset that also includes costs to operate, maintain, and eventually dispose of the asset. For example, an oil refinery may operate for 30 to 40 years (or more) with the costs of operation and maintenance over that life cycle exceeding the original capital construction costs by a multiple of ranging from 20 to 100. The cost of procuring or constructing an asset is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of total cost of ownership! Life cycle cost analysis provides an economic evaluation methodology for assessing the total cost of lifetime ownership of an asset; taking into account all the costs of acquiring, operating, maintaining, and eventual disposal of an asset. In order to provide an effective evaluation of costs over multiple years, LCCA relies on the concept of discounting that provides a method to convert future lump sum values, a uniform series of future values, or an incremental series of future values to a present value. The comparison of present values between potential alternatives provides a consistent methodology to evaluate the life cycle costs for alternatives that may have differing life cycles of asset acquisition and operation. Note that the concept of discounting can also be used to support a future cost evaluation (or an annual cost evaluation) between alternatives; although present value comparison is most common. The discounting conversions can also incorporate the impact of escalation when required. Discounting conversions are supported by mathematical formulas and tables, as indicated in the following table: The discount formula notation uses the (X/Y, i, n) scheme, which means find equivalent amount “X”, given amount “Y”, discount rate “i”, and the number of compounding periods “n”. When escalation is also factored into the discounting formula, it is represented by “e”. The following shows a simple investment alternative comparison evaluation: The typical steps involved in a life cycle cost analysis are:

1. Identify and define the problem requiring LCCA: This step involves identifying the potential opportunity (e.g. creation of a new asset, modification of an existing asset, retirement of an asset). Identify the potential time periods to be considered in the analysis. Identify the appropriate financial or other criteria upon which to base an eventual decision (e.g. present value versus future value, discount rate to be used in the analysis). 2. Develop potential alternatives/solutions to consider in the analysis: This step determines viable alternatives that will have economic impacts to be considered in the analysis. It may involve the consideration of capital and non-capital solutions. Often, making no change to the status quo is a potential option to be considered. 3. Develop the cost breakdown to support the analysis: The cost breakdown structure for the analysis will vary based on the particular problem under consideration and the alternatives, but at the highest level will typically include identification of acquisition costs (e.g. planning, procurement, construction) and sustaining costs (e.g. operating costs, utility costs, maintenance costs, repair costs, etc.). 4. Collect data and information to support the required cost and benefit values for each alternative: Effective analyses typically require a large amount of information to determine reasonable estimates for all elements of the cost breakdown structure. The analysis must address all elements for both acquisition and sustaining costs for each alternative; with the goal to provided sufficiently reliable unbiased estimates of both costs and benefits for each alternative. 5. Prepare the cost profiles and LCCA model for each alternative: Develop the cost profile (cost/benefit flow) over time for each alternative. Use the cost profiles to develop the LCCA model with appropriate discount formulas to support the financial analysis. The LCCA models should address all significant cost and benefit impacts (sufficiently complex but not overly complex). 6. Analyze results: Analyze the results for reasonableness. Prepare supporting analyses such as Pareto charts of key cost drivers or breakeven analyses. Test significant cost drivers with different assumptions or incorporate uncertainty analysis into the model to evaluate sensitivity for key cost/benefit drivers. Recycle to previous steps to adjust the model if warranted. 7. Communicate results and determine the course of action: Prepare reports to communicate the LCCA results to support decision making. Life cycle cost analysis is intended to measure cradle to grave costs for the asset or activity under consideration. It can be useful to identify key cost drivers to overall profitability and tradeoffs between competing alternatives. It’s a valuable technique to improve decision making be focusing on Total Cost Management, and improving long term cost effectiveness. The most effective impact from life cycle cost analysis is obtained when it is employed as a value improving practice during the early stages of project planning. It requires identification of alternatives, and good alternatives often require creation ideas. Focus on sufficient complexity to support the decision to be made. LCCA models should be flexible, traceable, and scalable; and the supporting data should be quantifiable and defensible. The techniques to perform life cycle cost analysis are not difficult; however they do require attention to detail to meet the objectives of the analysis. When performed well, they support better decision making by focusing on long-term costs and benefits to maximize capital investment performance. A Basis of Estimate (BOE) is the document that provides the contextual framework for the cost estimate to support informed and reasoned decision-making.

Cost Estimates are prepared to support decisions. At an early stage of project development, the decision may be to decide which potential alternative (or alternatives) should be selected to advance to the next stage of development; and eventually the decision may be to authorize full funding of a project based on the economic analysis and business case that has been prepared based on a project estimate. Most, but not all projects, are approved based on economic evaluations. Organizations attempt to maximize the value of their capital investments, seeking to fund from their limited capital budgets those projects that provide the highest rates of return. The cost estimate is critical to the economic evaluations determining rate of return and other financial metrics upon which a decision will be made. A decision can be made using a reasoned or intuitive process, and most often a combination of the two. Reasoned decisions are those established on objective assessments of all of the available facts and information. Intuitive decisions, on the other hand, are often based on past experience, and the personal perceptions and values of the decision-maker. In making capital investment decisions, organizations want to make reasoned decisions that are founded on comprehensive, clearly understood data and information. The estimate is an important component of that information, but if the estimate is presented as just a page of numbers then it provides no context to support its evaluation, and the subsequent decision to be made. A page of numbers or a bottom-line estimate value by itself cannot support reasoned decision-making. The Basis of Estimate (BOE) is the document that provides the contextual framework for using the estimate to support reasoned decision-making. AACE International Recommend Practice 10S-90 defines a basis document as “written documentation that describes how an estimate, schedule, or other plan component was developed and defines the information used in support of development. A basis document commonly includes, but is not limited to, a description of the scope included, methodologies used, references and defining deliverables used, assumptions and exclusions made, clarifications, adjustments, and some indication of the level of uncertainty.” AACE International Recommended Practice 34R-05 states that when prepared correctly “any person with capital project experience can use the BOE to understand and assess the estimate, independent of any other supporting documentation. A well-written BOE achieves those goals by clearly and concisely stating the purpose of the estimate, (i.e., cost study, project options, funding, etc.), the project scope, pricing basis, allowances, assumptions, exclusions, cost risks and opportunities, and any deviations from standard practices.” It is important to understand that an estimate is a prediction of the probable costs for a given scope of work to be completed in the future. An estimate by nature is uncertain, and although some of the information supporting the estimate is objective and factually based, much of the estimate is based on uncertainties that includes potential variations in scope quantification, pricing, required resources, execution strategies, etc. Every estimate is based on an extensive level of assumptions upon which the estimator must make an objective assessment to prepare a cost estimate that is comprehensive, reasonable, and sufficiently accurate to support the purpose and decision for which it is being prepared. Whether it meets these goals cannot be determined from the numerical presentation of the estimate. The Basis of Estimate provides context to the methods, practices, adequacy of the information and assumptions utilized in the development of the estimate. It provides thorough and reliable information to support effective estimate review and validation; and once approved can then be used to support sound business decisions for capital investment decisions. An important part of estimate validation and subsequent support for the investment decision is to understand the explicit or inherent cost strategy (cost effectiveness versus predictability) that may impact the eventual achievability of the estimate. The BOE is equally important for effective project controls, from establishing initial work packaging and contract management to supporting performance assessment and change management. It supports effective project schedule development and control. It provides the needed framework to understand the combination of identified scope and costs included in the estimate. AACE International’s Total Cost Management Framework identifies the Basis of Estimate as a required component of every cost estimate. To summarize, the main purpose of cost estimates is to support decisions to maximize the value of an organization’s capital investments. Without a Basis of Estimate, the decision maker must rely on an intuitive approach to decision-making. A well-written Basis of Estimate allows decision-makers to make reasoned and informed decisions, reducing the level of intuitiveness, to maximize cost investment performance for their organizations. |

AuthorConquest Consulting Group: A Leader in Effective Implementation of Cost Engineering and Total Cost Management Archives

January 2024

Categories |

- Home

-

Services

- Cost Estimating Services

- Cost Estimate Review and Validation

- Cost Risk Analysis and Escalation Studies

- Project Readiness and Performance Reviews

- Methods and Procedures

- Software Selection and Implementation

- Cost Estimating Database Development

- Historical Database and Benchmarking

- Organizational Development

- Estimating and Cost Engineering Training

- Construction Claims and Dispute Resolution

- Cost Estimating

- Cost Engineering

- About

- Blog

- Contact

|

Copyright © 2022; All Rights Reserved

|

Conquest Consulting Group

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed